|

|

||

|

Pro Tools

FILMFESTIVALS | 24/7 world wide coverageWelcome ! Enjoy the best of both worlds: Film & Festival News, exploring the best of the film festivals community. Launched in 1995, relentlessly connecting films to festivals, documenting and promoting festivals worldwide. Working on an upgrade soon. For collaboration, editorial contributions, or publicity, please send us an email here. User login |

Budhia Singh—Born to Run, alias Duronto, Review: Marathon gone

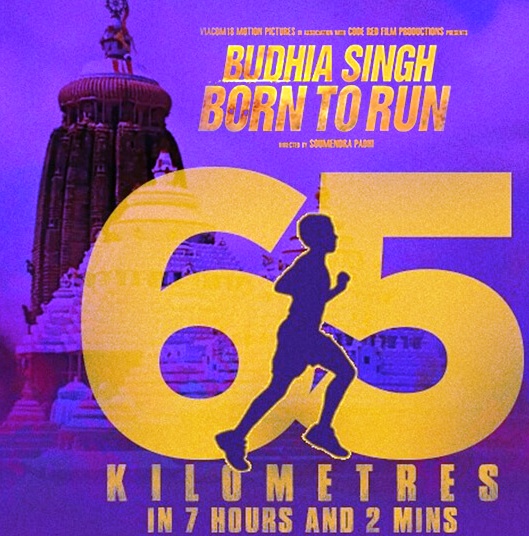

Budhia Singh—Born to Run, alias Duronto, Review: Marathon gone Running is good for health. Making films on running and runners is not a bad ploy for a production house to get a run for their money, or money for your run. Milking the genre without substantial innovation might not be such good idea, though, and the box-office run might be as short-lived as, or, in fact, much shorter than, the apparently aborted career of India’s child wonder, Budhia Singh. Based on a true story, Budhia Singh—Born to Run was initially titled Duronto, after the super-fast trains that run across the length and breadth of India, with very few stops. The Indian Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) certified the film for release under that title. However, the film has been released with an amended moniker. While titling it Duronto would not have made much of a difference to the film, Born to Run conveys the impression that it is the story of a person who ran all his life, and broke many records. What we are shown, instead, is a child being trained to run, and creating ripples with his achievements, over a period of about one year—only! Budhia Singh—Born to Run is about real characters and real incidents, coupled with subjective interpretations, and inconclusive scenes galore. In 2005, a four year-old boy named Budhia Singh (Mayur) is sold into slavery by a miserably poor mother Sukanti Singh (Tilottama Shome), who has an alcoholic husband and works as a domestic help. He is rescued and trained by an upper middle class Judo champion, Biranchi Das (Manoj Bajpayee) who runs a training centre for homeless children, who he provides with food, shelter and clothing. Das accidentally discovers that the boy can run for hours, without a break, a natural, with inexhaustible stamina, and decides to groom him for marathon runs, with an eye on the 2016 Olympics. It’s not smooth sailing, as can be expected. Biranchi has the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF), stationed nearby, on his side, having trained some of their personnel in judo, but the Child Welfare Committee of Orissa (now renamed Odisha) state, led by a woman called Mahasweta (Chhaya Kadam) frowns upon his subjecting Budhia to “child labour”. Politics are at play too, with Das willingly accepting money from the leader of the opposition in the state assembly for dubious deals. Some of Biranchi’s orchestrated demo runs make headlines and garner TV coverage (by Pushkaraj Chirputkar, Sayalee Pathak). A foreign female film-maker arrives to make a documentary on the marathon boy. In parallel developments, Sukanti, after her husband’s death, is incited by a slum leader (Gopal Singh) and a CWC official (Gajraj Rao) to make serious allegations against Das, while he is also accused by the administration of embezzling funds collected under a Budhia trust, and sent to jail, while Budhia is whisked away to a state-run sports centre. Ten years later, Budhia is still there. Nipped in the bud? Not autobiographical, the film is not biographical either. And if we do stretch the definition, it is the biography of Biranchi, and not Budhia. Before shooting began, the team spent a lot of time with Gita Panda, wife of late Biranchi Das, journalist Sampad Mohapatra, lawyers and many others who were associated with Budhia and his coach. Surprising, then, that the narrative is still full of holes. Absolute credit to the writer-director Soumendra Padhi (software firm in Hyderabad; moved to Mumbai in 2006 to study film-making and animation; joined Code Red Films as an assistant director and simultaneously directed short films, documentaries and music videos; this is his debut), for naming some names, but similar minus marks for not naming many others. On the other hand, he may have had to make amendments under the directives of the CBFC, on sensitive issues. Politics form a core sub-text; the religious significance of the state of Orissa and the city of Puri as the land of Lord Jagnannath, with chants of Jai Jagannath rending the air as the boy takes to the long, winding roads, is another element. It is hard to find any positive and conscientious characters in the tale. All are either grey, or downright black. Ah, yes! Gita, Biranchi’s wife, looks after all the adopted boys like her own, even after she gives birth to first baby, a boy, later in the story. All possible tropes are employed as the film walks along, breaking into a run only in a couple of scenes that too end in unfulfilled expectations. TV reporters, doctors and CPRF personnel are portrayed as stereo-types, with one character pacing up and down in stagey anxiety, inter-cut with parallel developments. Casting is a mix of praiseworthy and poor. From all reports, Biranchi looked nothing like Manoj Bajpayee, whereas Mayur is very close to Budhia. Several Marathi actors, most of them incredibly talented, are wasted, and their accents nowhere near the Odiya touch that was mandatory. Only two dimensions of Budhia are explored: his bed-wetting habit and his ability to run. Okay, so he was only 4-5 years old in the story, but then it was the job of the writer-director to find or create other aspects that keep the viewer engaged. Manoj Bajpayee never lacked sincerity. That is not under the scanner. Does he appear convincing as a manipulative, egotistical judo champion? No. Does his permanent frown add to his performance? A definite “No”. Tilottama Shome (Monsoon Wedding, Aatma, Qissa) is such a versatile actress that her one ‘come hither’ smile, after several scenes of misery, stamps her authority. Gopal Singh (born and brought up in a very small town in Odisha’s neighbouring state of Chhattisgarh; seen in Ek Haseena This, Company, Page 3, Traffic Signal) and Gajraj Rao (Bandit Queen, Dil Se, Talvar; co-producer for Code Red Films, the banner, which is headed by Subrat Ray and Rao) are superb, as is their wont. Shruti Marathe as Gita is passable. Chhaya Kadam, immensely talented (Highway—Ek Selfie Aar Paar, Marathi), is hampered by Odiya, Hindi and English accents. Pushkaraj Chirputkar and Sayalee Pathak as reporters are no different from any of their ilk seen in a hundred other films. Mayur Patole as Budhia Singh, is a quite a kettle of fish. Director Soumendra Padhi had auditioned 1200/3000 kids (figures vary) for the title role, from different states in the country, including Odisha, Chhattisgarh, Delhi and the two Maharashtra cities of Mumbai and Pune, before he finalised Pune a slum-dweller’s son, Mayur, for the role. He is one in 3,00,000, more than a natural, acting and reacting on cue, spontaneous and vivacious. One can safely assume that the National Award for the Best Children’s film must have been decided largely on his performance. He saves the film...almost! If you want a reason to see the film, he is it. Incidentally, a 30-minute documentary was made on Budhia Singh, in 2010, by Gemma Atwal, called Marathon Boy. (Read below). Trailer: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YGft9XiX4bs Rating: **

Budhia Singh, with senior journalist, author and film-critic Bharathi Pradhan and Mayur Patole, at a press preview of the film, held in Mumbai, late on 04 August 2016. From Bharathi's public Facebook page. Permission sought. Background material, culled from various media sources, for reference only News report, Early July 2016 Media reports surface that “Budhia Singh had gone missing from his Sports Hostel since last two months.” News report, July 16, 2016 The Child Welfare Committee (CWC) of Khordha, Odisha, on Saturday issued a notice to a Mumbai-based film producer Subhamitra Sen, who has been making the film titled ‘Budhia Singh: Born to Run’, seeking the whereabouts of marathon boy, Budhia Singh, who was reportedly missing for over a month. “The film production house’s PR department told CWC that Budhia was not missing. However, they did not reveal where the boy was staying. Film director Soumendra Padhi, in an SMS message, said that Singh was not missing. The CWC wondered how did he know Budhia was not missing?” His hostel had no information on the current whereabouts of the marathon boy, but it said Singh had taken leave from the school authorities till June 27. The sports hostel reopened on July 4, but Singh did not return. News report, Jul 28, 2016 Wonder boy Budhia Singh and his mother returned to Bhubaneswar yesterday, from Mumbai, after a one-month vacation. "I was on a holiday with my mother for the past one month to different parts of the country,” Budhia told reporters on his arrival at the Biju Patnaik International Airport here. Excerpts from Runner’s World, August 2008, By Bill Donahue On the morning of May 2, 2006, a little boy stepped into the streets of Puri, in running shoes. Budhia Singh was 4 years, 3 months old. A slum kid, he wore bright red socks and a collared white tennis shirt that drooped to mid-thigh. His task that morning, as prescribed by his coach Biranchi Das, a one-time all-India judo champ, was to run home: 43 miles (69 kms), back to Bhubaneswar,. If all this sounds stranger than a fairy tale, consider that Budhia is now, at age 6, a celebrity in India. He’s starred in a popular music video in which he runs, does judo, and unleashes a hip-hop chant, “I am Budhia, son of Orissa.” As he stood in Puri, Budhia was said to have run six half-marathons and train 120-plus miles a week. Sometimes he ran barefoot on asphalt. Almost always, he ran without hydrating. “If he drinks while running,” reasoned Das, “he will go weak.” Das had alerted the media and worked his connections with the Central Reserve police force. A squadron of officers and cadets in khaki shorts was ready to run with the boy. Three days after Budhia’s Puri run, Orissa’s Minister for Women and Child Development would sweep in to arrest Das, who was also the boy’s foster father, on charges of child cruelty. Later, newspapers would air lurid accusations. Budhia’s mother alleged last summer that Das hung her son upside down from a ceiling fan, splashed him with hot water, and branded his skin with the words “Biranchi Sir.” Budhia himself told reporters, “He locked me in a room for two days without food.” Sukanti Singh took her son back from the coach. All very damning, except that a medical report, conducted by a neutral forensics specialist, Sarbeswar Acharya, revealed that the scars on Budhia’s body were three to six months old. They were not caused by scalding water, Acharya opined, and not corroborative of Sukanti’s claims. And a newsbreak this spring only deepened the mystery. On April 13, Biranchi Das, 41, was murdered—shot dead outside his judo hall. The prime suspect, a gangster named Raja Acharya, who faces some 30 unrelated counts of extortion, murder, and kidnapping, is now in jail, awaiting trial. He was infatuated with a lovely Indian actress, Leslie Tripathy. Police speculate that Das irked the gangster by cautioning him to stop harassing Tripathy. If they’re right, perhaps Das died for honour. Then again, you could ask why he was hanging out with a violent thug like Acharya in the first place. And was he himself the sort of tough who might thrash a child? Back in Puri, Biaranchi bent to the ground and tied Budhia’s shoes. Budhia started to run, at roughly 10 minutes a mile, up a long, slight incline, past roadside shops where vendors sold milky chai for 10 cents a cup and past bald patches of land where long-tailed monkeys crouched by the road, watchful and still. Budhia kept going. He crossed a bridge over the River Kushabhadra and passed the fishing village of Chandrabagha. With temperatures climbing into the 90s, Budhia drank only a touch of lemony water. He tired. Then, three miles short of his goal—seven hours, two minutes into his run—Budhia collapsed from exhaustion. He began vomiting and convulsing. Over and over, he bit at the arms of Jyotsna Nayak, the doctor tending to him. Nayak later told a British film-maker, “Brain irritation was there. Had I not been there, he certainly would have died.” And large questions seemed to hang in the air: Do coaches and parents have the right to conscript children to chase after glory? Who sets the rules? Budhia Singh was born in Bhubaneswar’s Gautam Nagar slum, in a shanty that has since been razed to make way for the railroad. His mother worked, in Indian parlance, as a peon. She did domestic chores, earning $6 a month. Budhia’s father, meanwhile, was an alcoholic addicted to ginger—dirt-flecked firewater that women sell from battered metal bowls by the roadside in India. He was unemployed, a beggar who contributed nothing to his family’s welfare. Budhia’s parents knew Biranchi Das, who was the president of their slum in Bhubaneswar, the owner of a hotel, and a partner in his family’s taxi business. For more than a decade, Das had run an esteemed judo hall, handpicking athletically promising boys and girls from the slums and subjecting them to an almost paramilitary training regimen with twice-daily workouts, strict dietary rules, and classes on combat theory. Seven of his students have become national champions, and more than 1,200 have launched careers with the Central Reserve police force. I met Das four months before he was killed. He was stout and bearded, rippling with muscles despite a little potbelly, and he exuded the dark, burly beneficence of a Mafia don. In 2003, he said, Sukanti asked if 1-year-old Budhia could bunk at the judo hall. “She had three daughters, all older than Budhia,” Das said, “and already she’d sold the two oldest into servitude, as maids. She told me, ‘I can’t afford this boy. I can’t feed him. Take him.’” Das said no—Budhia was too young for judo. But about six months later, according to Das, the boy suffered an accident. Riding the crossbar of a neighbour’s bicycle, he crashed, fracturing his ankle and shredding the skin on his leg. Untended, the wound festered and got infected. When Sukanti at last took her son to the hospital, doctors advised amputation. Terrified, she returned to Das. This time he said he’d care for the boy. Budhia lived with Das and his wife for six months, until his leg healed. Then the boy went back to his mother, only to be hit by tragedy. Inside a month, Budhia’s father died. Soon after, Das asserted, Sukanti sold her son to a bangle vendor, a man who sold peanuts and gum from his bicycle, with the expectation that, in time, Budhia would work as an assistant. “The vendor didn’t take care of Budhia,” Das said. “When Budhia visited me after one month, his skin was pale, his clothes were dirty, and he had sores on his body.” Das said he bought the boy back for $20. Then one day when Budhia was just 3, the boy cussed. Das punished him, forcing him to run around a dirt oval “until I get back.” Five hours later, Budhia was still running. Soon Das decided that Budhia would become the first Indian runner to win an Olympic medal. He began training the boy, riding on his bicycle as Budhia ran—four miles a day at first, then six, then 10. In time, crowds of adoring fans joined the runs, trotting behind the boy or rolling beside him on bikes. In October 2005, Das took Budhia, then 3, to his first race—a half-marathon in Delhi. Race officials forbade Budhia to start, but no matter. He was the darling of the 6K fun run, and the It Boy of a post-race gala. British decathlete Daley Thompson tried to score a kiss from Budhia, but Tim Hutchings, international administrator for the London Marathon, fulminated, “For a child of 3 to be training hard is verging on criminal.” By now, a British film-maker (Gemma Atwal) was tracking Budhia’s story, making a half-hour TV documentary, and Das was hatching intricate plans. He decreed that, after the Puri run, Budhia would run a marathon in Nayagarh. “After that,” he said, “he’ll go to Madras, and then there’s a race in Cochin, and onto Guwahati. After this we will take him to some events abroad.” He never competed in these races. After his Puri run, Orissa’s child welfare department issued a medical report finding him “undernourished, anaemic, and under cardiological stress.” The agency banned all children from entering distance races before the age of 14. In India, the ruling was largely seen as ridiculous. “How self-indulgent and naive can our liberalism be?” railed columnist Barkha Dutt. “This is a chance for a poor slum child to break down the class divide and travel on the same superhighway to success as everyone else.” Snubbing officials, a public poll named Budhia the second most popular person in Orissa. A steel company hired the boy as a spokes-mascot, and a Dubai businessman flew Budhia and his coach to the United Arab Emirates for a splashy getaway at an amusement park. Then came the video that nearly deified Budhia. “We hoped the song would clear many misconceptions about the child,” said producer Rajesh Kumar Mohanty. “We have tried to compare him with the mythological Lord Krishna.” Gemma Atwal, maker of the documentary, Marathon Boy, on the Budhia story (excerpts) (Gemma has worked as a freelance director and producer on a variety of international factual and observational documentaries. She has also spent three years working as a development producer for independent UK production houses, on projects in human interest, wildlife & adventure, and science programming. Before making documentaries, Gemma spent four years working as a business journalist in West Africa and South-East Asia. Marathon Boy is her first feature documentary. In her spare time, Gemma is a keen runner and snowboarder). 16 March 2011 Six years ago, a colleague of mine sent me a link to a story on the BBC News website. I have run upwards of a dozen marathons and could not fathom how such a small boy would possess the necessary stamina or resistance, quite apart from any ethical considerations. There was a small part of Biranchi Das, the boy's coach, that reminded me of my own adoptive father, who took in a rag-tag band of eight unwanted kids from diverse Hindu, Sikh and Muslim backgrounds, and gave them a stable upbringing. It was my personal circumstance that also drew me to other characters in the story. Similar to Budhia's mum, my birth-mother belonged to the lowest Hindu caste and lived in extreme poverty. But a twist of fate led me to be adopted by a couple in England, and I lived an entirely different life filled with possibility. Dreams or nightmare? In 2005, I managed to locate three-year-old Budhia. I arrived just before dawn, wondering if anything more than a disturbing freak show would be in store. It was still dark but I could just make out his tiny legs swinging beneath a bench in what would become his trademark red pumps - they did not even make trainers his size. The moment I started to approach, Budhia leapt up onto the bench and started to perform this giddy song and dance for me while simultaneously making the victory sign with both hands. I was horrified at this little marionette show laid on for me and urged my translator to tell Budhia that he was not required to perform for me. Looking at Budhia in those first few moments, I did not know if his story would turn out to be the stuff of Bollywood dreams or a child's nightmare. It turned out to be both. Today, Budhia is a boarding pupil at a government-run sports hostel in Orissa State. He has been assigned a new coach, though he is no longer required to run the distances he ran before and his weekly schedule includes hockey, discus and football. In 2006, Budhia Singh was taken for medical tests - he was banned from long distance running. I asked his new coach if he sees Budhia becoming a running champion: "Now is not the right time to say if he can make it, but if you come back in 10 years time I will tell you!" Budhia has also been awarded a government scholarship to one of Bhubaneswar's most prestigious English Medium Schools. A peon's child destined to caste-bound misery is now mingling and learning among his country's elite. On his first day, Budhia addressed the entire school: "I am Budhia Singh. You will all be my friends and in return I will help you learn how to run!" He recently won the egg and spoon race in his first school sports day. It is difficult to gain a full sense of how Budhia is processing the events in his life and the long-term impact. The last time I saw him he seemed brooding and insular. He would stare down a lot. He said nothing. I said nothing. Questions seemed to put him under enormous pressure and I did not want that. Instead, we held hands and listened to the other children laughing and creating a din outside. On the last occasion that I saw Biranchi Das, he told me: "Budhia is a very good child. He and I had a dream. It was not fulfilled. That is the agony for me. In Russia, Korea and China, they start training athletes at the age of three. If you don't take risks you don't get results. I am the person who took risks with Budhia, and I got results." Perhaps some people would say that Budhia has been released from the man who enslaved him, but for this small boy, he's lost the only loving advocate and mentor he ever had 06.08.2016 | Siraj Syed's blog Cat. : Bill Donahue Biranchi Das Gajraj Rao Gemma Atwal Manoj Bajpayee marathon Mayur Patole Odisha Olympics Orissa Soumendra Padhi Independent

|

LinksThe Bulletin Board > The Bulletin Board Blog Following News Interview with IFTA Chairman (AFM)

Interview with Cannes Marche du Film Director

Filmfestivals.com dailies live coverage from > Live from India

Useful links for the indies: > Big files transfer

+ SUBSCRIBE to the weekly Newsletter Deals+ Special offers and discounts from filmfestivals.com Selected fun offers

> Bonus Casino

User imagesAbout Siraj Syed Syed Siraj Syed Siraj (Siraj Associates) Siraj Syed is a film-critic since 1970 and a Former President of the Freelance Film Journalists' Combine of India.He is the India Correspondent of FilmFestivals.com and a member of FIPRESCI, the international Federation of Film Critics, Munich, GermanySiraj Syed has contributed over 1,015 articles on cinema, international film festivals, conventions, exhibitions, etc., most recently, at IFFI (Goa), MIFF (Mumbai), MFF/MAMI (Mumbai) and CommunicAsia (Singapore). He often edits film festival daily bulletins.He is also an actor and a dubbing artiste. Further, he has been teaching media, acting and dubbing at over 30 institutes in India and Singapore, since 1984.View my profile Send me a message The EditorUser contributions |